Today’s featured article from the sidebar of the What Others are Writing Section on the Homepage comes from a new source, Texas National Security Review, more on them in a minute. Once again, there were several candidates for today’s feature with a special shout out to Tehran rekindles Nagorno-Karabakh peacemaker role – Asia Times and As If the Platypus Couldn’t Get Any Weirder – GIZMODO (which should probably become a daily stop). Honestly, there are so many candidates today it was hard selecting only three for this and I am going to cheat and include a second article from the sidebar in the main discussion also! Anyway, if you haven’t already done so, head over to the front page and check out some of the other candidates for today’s post!

The Texas National Security Review offers deep dives into policy, research and analysis. I have not read many of their articles, which could probably more accurately be described as publications or papers, but what I have read, all have been impressive. From their about page:

The Texas National Security Review is a new kind of journal committed to excellence, scholarly rigor, and big ideas.

Launched in 2017 by War on the Rocks and the University of Texas, we aim for articles published in this journal to end up on university syllabi and the desks of decision-makers, and to be cited as the foundational research and analysis on world affairs….

By focusing on the production and publication of top-tier scholarly work that serves both academic and “real-world” audiences and goals, we aim to create something we know is difficult but we believe is well worth pursuing. The print edition comes out quarterly and will be made available online, for free, for everyone. The online edition also features roundtable-style debates, discussions, and book reviews.

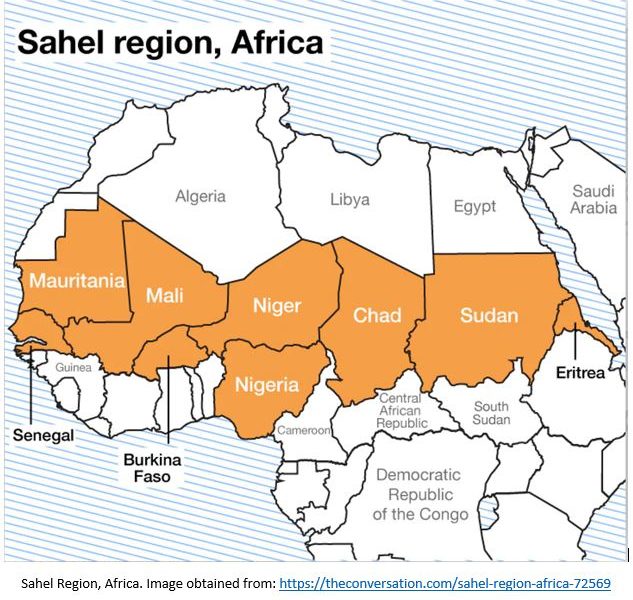

Today’s featured article, France’s War in the Sahel and the Evolution of Counter-Insurgency Doctrine offers a deeeeep dive into France’s fight in the Sahel or central region of Africa that I simply cannot properly summarize here.

Why this is important

This is important because the greater fight against al Qaeda and ISIS is not over and we will continue to have troops deployed in this region of the world. Even though most of the policy makers have moved on to the Great Power Competition, this particular region will remain volatile and potentially part of a proxy war that could be used to tie up the resources of others. Oh and then there is this, French airstrikes kill over 50 people in Mali from DW today:

French forces said they have killed more than 50 terrorists and captured 4 four others in an operation in Mali. The French defense minister said the action was a major blow to al-Qaeda….

The French operation took place in an area near the borders of Burkina Faso and Niger where government troops are fighting an Islamic insurgency, Parly said after a meeting with members of Mali’s transitional government in the capital city of Bamako.

There is a lot more there in that report and I encourage you to follow the link and read the entire article. Before we dive into today’s feature, let’s take care of some housekeeping and define what the ‘Sahel’ is anyway. From The Conversation:

The Sahel region of Africa is a 3,860-kilometre arc-like land mass lying to the immediate south of the Sahara Desert and stretching east-west across the breadth of the African continent.

A largely semi-arid belt of barren, sandy and rock-strewn land, the Sahel marks the physical and cultural transition between the continent’s more fertile tropical regions to the south and its desert in the north.

The report continues with its significance and the threat posed by Islamic extremism there:

Culturally and historically, the Sahel is a shoreline between the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa. This means it is the site of interaction between Arabic, Islamic and nomadic cultures from the north, and indigenous and traditional cultures from the south.

Concerns abound over the region’s vast spaces, often beyond the reach of the state, in an era of violent criminal and political movements operating across borders. The Sahel also suffers from ethno-religious tensions, political instability, poverty and natural disasters.

Back to our featured article. Michael Shurkin opens with a little history that is key to understanding the region and France’s role there.

Criticism of French military operations in the Sahel region of Africa raises questions about the French army’s heritage of colonial and counter-insurgency (COIN) operations and its relevance today. The French army is heir to practices and doctrines that originated in 19th-century colonial operations and the Cold War. Common features of French approaches have been a de-emphasis on military operations and the need for a population-centric focus that emphasizes economic, psychological, and political actions intended to shore up the legitimacy of the colonial political order. After the conclusion of the Algerian War in 1962, the French maintained some of these practices while slowly adapting to the post-colonial political context. Operation Barkhane, which began in 2014, reflects that new doctrine, meaning that the French military is limiting itself to focusing on security in the anticipation that others will do the political work. This is complicated by the fact that the French presence constitutes a political intervention, even as the French strive to avoid political interference.

We have discussed this fight briefly here and The New York Times’s, Ruth Maclean, does an excellent job of summarizing the conflict in Crisis in the Sahel Becoming France’s First Forever War. Critics have labeled the conflict a ‘colonial campaign’ that is ‘doomed to follow the course of the U.S. war in Afghanistan.’ So what is the purpose of Shurkin’s paper:

The purpose of this paper is to explore the French military’s COIN doctrine and practices as they have evolved from their 19th-century origins to the present day. I wish to examine French strategy in the Sahel, and specifically Operation Barkhane, in light of the evolution of French doctrine and practice. Much of the story of French COIN is familiar to Americans because of U.S. interest in the subject after 2003, when they viewed it as a model for U.S. counter-insurgency operations. 8 There are, however, certain aspects that Americans have overlooked, and in any case, the evolution of French doctrine after the end of the Algerian War in 1962 is largely unknown in the United States.

Like I alluded to earlier, this is a very deep dive that covers France’s military operations and the ‘global approach’ that is rooted in colonialism. Mr. Shurkin breaks down the paper into two parts, the history of French COIN and a close examination of current French Operations there.

The standard narrative of French COIN doctrine focuses on either the colonial doctrine of Gallieni and Lyautey or the Cold War-era doctrine associated with the wars in Indochina (1945 to 1954) and Algeria (1954 to 1962) and men like David Galula, Jacques Hogard, and Roger Trinquier. There was a third generation of French COIN doctrine developed in the 21st century in response to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, which prompted French officers to dust off the Indochina-era doctrine and update it. Each generation of France’s COIN tradition merits discussion, for the differences are as noteworthy as the similarities. In each instance, what is regarded as “doctrine” is often more accurately described as “myths” or “representations” regarding the French army’s approaches and experience. It has to do with the stories French army officers tell themselves, or about how they imagine their predecessors.

This is about the time I realize that I am not nearly as well read as I kid myself and like to believe! There is so much here that I could not possibly do it justice even attempting to summarize what Shurkin is saying. The level of detail in this paper is truly impressive as Shurkin dives into ‘The origins of population centric warfare,’ ‘Colonial Doctrine to COIN,’ ‘A Post-Colonial Approach’ and the ‘The French Army Revisions to COIN from Iraq and Afghanistan.’ In Shurkin’s discussion on ‘Current French COIN Doctrine’ he writes:

In April 2013, it [the French Military] released a joint publication, Contre-insurrection. Contre-insurrection has much in common with the 2009 Doctrine de contre rébellion, though it is a richer text that reflects a deeper meditation on the realities of post-colonial operations and the implications for “intervention forces” operating in a sovereign host nation. At last, one sees a major shift away from colonial doctrine. Theoretically, Contre-insurrection has profound relevance for current French activities in Mali and sheds a lot of light on what the French are doing.

To be clear, this document re-treads familiar ground. Gallieni, Lyautey, and the pantheon of Indochina-era COIN theorists are all present. There are endorsements of the oil spot, quadrillage, and ratissage, and talk of nomadizing units designed to bring insecurity to insurgents outside the oil spots. Yet the text is concerned with their relevance to 21st-century conflict, and it makes it clear that the context for the policy has changed. France is no longer in the business of “pacification”:

The historical method of the “oil spot” invented by Gallieni during the pacification campaigns is no longer directly transposable and must be updated. For one thing, this method corresponded to the objective of conquest, which is no longer the current goal. For another, the reduced size of ground forces no longer permits the realization of this kind of maneuver without dangerously stripping the secured zones, and it is extremely harmful to the action of the Force to let a secured zone fall into the hands of insurgents. 114

This text is revealing. First, the point is no longer colonization, which was the objective of Lyautey’s progressive occupation of Morocco. Second, there is the fact that the French army in 2013 was less than half its size just prior to the end of the Cold War. Without saying so directly, Contre-insurrection is acknowledging that there will be no more wars on the scale of Indochina, let alone Algeria. From now on, the model is Operation Bison and the war in Chad.

To get the full picture of what Shurkin is stating you really need to read the entire paper but he does highlight what the French Military’s joint publication states that an intervening force should do:

-

- Respect the preeminence of the system and the political decisions of the host country;

- Understand the extremely strong interaction between their action and the political nature of the counter-insurrection;

- Promote the adherence of local leaders and the population to the political process of reconciliation;

- Support (and sometimes reinforce) the legitimacy of public powers, notably those of the local security forces, by taking every opportunity to improve their abilities, promote their ethics, and make them more responsible and raise their value in the eyes of the population;

- Enhance and assure the protection of local loyal elites (provided they are good examples), for they constitute the best connection between the population and the counter-insurrection, and the political alternative offered by the indigenous government; and

- Demonstrate great firmness toward locals at all levels who do not act respectfully of the rights of their population. 118

Shurkin dives into all the above points and notes their limitations and how they are currently being employed. His conclusion is really an endorsement of why we should read the entire article and is a testament to why this matters not only in looking back on the conflicts of Iraq and Afghanistan, but also to look toward the future and the unwritten about conflicts that we are currently engaged in.

French strategy in the Sahel might yet work. But it will take a long time, and it is not clear why anyone should expect otherwise. In the meantime, France will be tempted to be more colonial, in the sense that it will want to intervene in politics more directly. Alternatively, it might risk doing less, and perhaps let Sahelian governments feel more anxious about their fate. It has no good options. From an American point of view, it is refreshing to see how modest French ambitions are given the U.S. propensity for dreaming big. Dirou, in his unpublished memoir, references Foch’s arguments about seizing opportunities to act decisively. In modern conflicts, Dirou writes in his manuscript: “We might consider a decisive battle as one of which the product is the opening up of immediate strategic possibilities with the potential to influence profoundly the course of events in an enduring fashion.” 142 Right now, the French are aiming for little more than creating “strategic possibilities” in the hope that its partners might exploit them.

There really is so much in France’s War in the Sahel and the Evolution of Counter-Insurgency Doctrine that I simply cannot do it justice by attempting to summarize it and can only recommend that you read the entire paper.