Today, we have a double feature from the sidebar of the What Others are Writing Section on the Homepage that come from two of my favorite sources, the Modern War Institute and The United States Army War College: War Room . Both are a must stop for professional development that I regularly link too. The two other articles that come in for honorable mention are: In ruins, Syria marks 50 years of Assad family rule – AP and SITREP: Azerbaijan’s drone war expands with Reaper-like TB2 – ARS Technica Both are very good articles that provide very different views of conflict today; a family dynasty and cutting edge technology. If you haven’t already done so, head over to the front page and check out some of the other candidates for today’s Featured Article, there are A LOT of them today!

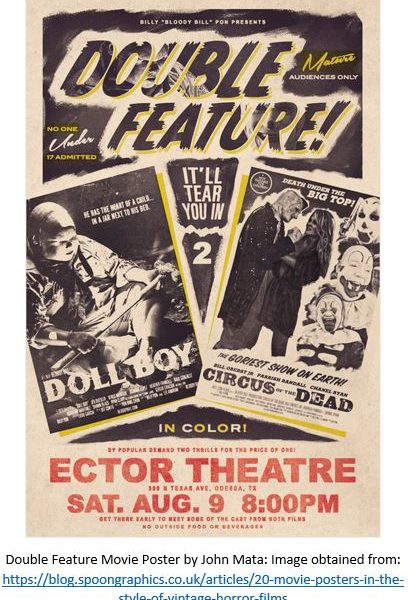

Our Double Feature:

American Military History is Wrong – Modern War Institute

Military Geography And Military Strategy – War Room

Why These Are Important

The study of history and the physical terrain of war are essential to understanding how a conflict will be fought and crucial in setting expectations not only for the war fighter but the political apparatus needed to support military actions. Without proper expectation management through historical perspective and strategic guidance most military operations are doomed for failure.

American Military History is Wrong – Modern War Institute by Glenn M. Harned

I will admit I was skeptical of this article at first (that is why it actually was posted yesterday). I thought it was going to be another, ‘we are doing everything wrong’ crisis of confidence post but my initial impression was completely off base. The proper understanding of historical conflicts are crucial not only to the war-fighter but the public that supports them at home. Here is the setup:

American military personnel study history as an essential component of their professional education. Military history provides the analogies by which they communicate, and the lens through which they view current military problems. Phrases such as “another Pearl Harbor” or “another Maginot Line” or “another Vietnam” convey common perceptions of the past and influence military professionals’ common thinking about the present and future.

But what if the military history they study is wrong? What if the military history they study fosters a strategic culture that is inconsistent with their strategic reality?

When we look at war we often look at it within a defined parameter of dates, The Revolutionary War – 1775-1783, Civil War – 1861-1865, WWII – 1939-1945, Vietnam – 1960-1975 you get the point. According to the author:

Central to the study of American military history in the last three decades of the twentieth century was The American Way of War, a history of American military strategy and policy written by Professor Russell F. Weigley. He argued that the American way of war is based on a strategy of annihilation: the aim of the US armed forces in war is to destroy the enemy’s capacity to continue the war, so that the enemy’s will collapses or becomes irrelevant.

But what if the period of annihilation that brackets our war perspective in the dates that we choose to define conflict are wrong and mislead our perception of the effort it takes to fully achieve victory? To highlight this mis-perception Harned first takes a look at WWI (emphasis mine):

After the armistice in November 1918, the US Army participated in the Allied Powers’ occupation of Germany until the peace treaty was signed at Versailles in July 1919, and then most of the US soldiers came home to celebrate the victory (although even in this case the First Division remained part of the Allied Army of Occupation until July 1923).

He then goes on to ‘re-frame’ the dates of some of our other conflicts and drives home expectation management by bringing this forward to our most recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The American Civil War did not end at Appomattox, any more than the American War of Independence ended at Yorktown, World War II ended on V-E and V-J Days, or the Iraq War ended with the fall of Baghdad. After Yorktown, Washington furloughed most of the Continental Army but it remained an army in being until after the British withdrew from New York City on Evacuation Day—November 25, 1783—two years later. Twelve years of Northern occupation and counterinsurgency followed Lee’s military surrender at Appomattox, until the Northern and Southern leadership reached a political settlement in the Compromise of 1877 at the Wormley Hotel in Washington, DC. The compromise resulted in the inauguration of President Rutherford B. Hayes and the withdrawal of Northern troops from Louisiana and South Carolina. The US military occupied Japan and Germany until peace treaties were signed in 1952 and 1955, respectively. The fall of Baghdad ended major combat operations in Iraq, but martial law was not declared or established. US commanders believed their mission was complete when the Iraqi army collapsed. They ignored their legal and moral obligations to restore order and impose interim military governance over occupied territory. Despite the futile efforts of leaders like Gen. Eric Shinseki who knew better, the poorly planned and executed consolidation and stabilization effort resulted in an eight-year insurgency ending in a unilateral US withdrawal, not a peace treaty or a stable and enduring political outcome.

For me, looking at the recent conflicts from this perspective is unbelievably frustrating in that I do not believe most people truly understood the commitment we were potentially making in Iraq and Afghanistan. Maybe I should have, especially considering my training in unconventional warfare, but I missed it while the conflicts were raging. Only now, given the benefit of time and distance do I see it more clearly. We always said it was a generational fight, but for some reason, I didn’t think we would actually fight for a generation! So why is this important? I will only list two of Harned’s seven reasons because you really, really should read the entire article for yourself:

- Major combat operations are critical but not decisive. Military victories are transitory and at best establish the conditions necessary to achieve a favorable and enduring political settlement.

- Post-combat consolidation of military gains, stabilization of the conflict-affected area, and reconciliation of the warring parties are decisive because they translate military success into a favorable and enduring strategic outcome.

Harned makes his case and then applies this train of thought to future potential conflicts which I believe is of crucial importance for the public perception and expectation of war. He leaves us with this:

Outcomes-based strategies will be critical to reversing the trend of US armed forces winning every battle, prevailing in every campaign, and losing every war it has fought since 1955. The first step: fostering a more accurate understanding of American military history, especially in professional military education.

Which brings us to part two of our double feature.

Military Geography And Military Strategy – War Room by Thomas Bruscino

I mean how does that title alone not just reach and grab ya? AMIRIGHT! I have always been a ‘map guy’ that wanted to look at and understand our piece of a larger puzzle and when I read Kaplan’s Revenge of Geography , my mind was blown. It took a bunch of tiny, dimly lit, flickering lights in my mind and supercharged them into a full-blown Charlie Brown, “THAT’S IT!” In our double feature, Bruscino makes the case this way:

Military strategy depends on geography to a far greater degree than what is currently practiced or taught. Even if military strategists go past ends in the oversimplified heuristic and get into the ways and means, neither of those categories encourages a greater focus on the unique characteristics of geography as a key factor of making military strategy….Where geography plays its more traditional role, it is part of assessing or framing the environment—but a very small part. Perhaps because of the last few decades of counterinsurgency-type fights, understanding the strategic environment in American military strategic theory and doctrine has become heavily focused on peoples and cultures, best evidenced by the attempts to map the so-called “human terrain.”

In my opinion, the ‘physical terrain’ and ‘human terrain’ are inextricably linked and must be studied at the same time. Bruscino continues:

If physical geography has a place in military affairs, it is generally in military intelligence, and there it is shunted off to geospatial sub-specialists. The older concept of geopolitics, which directly related features of physical geography to concepts of political, military, and naval advantage in peace, became a sort of synonym for so-called realist approaches to international relations, losing its focus on physical characteristics, which is why Robert Kaplan needed to write about The Revenge of Geography in 2012. As a result, a deeper understanding and application of military geography is not a part of the study, practice, planning, or even execution of war for senior military professionals responsible for military strategy. That is a mistake.

To make his case, Bruscino leans heavily on Alfred Thayer Mahan, an American Naval officer that lectured at the Naval War College in the 1880s that wrote on the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, who Kaplan also extensively quoted in Revenge of Geography. So why is an 1880’s Naval War College lecturer important today? Broscino states:

…close consideration of what the geographic features of the Gulf and Caribbean might mean for wars between the United States and other powers clarifies many things. For one, the course, conduct, and outcome of the 1898 Spanish American War in the region makes far greater sense. The military geography fundamentally shaped the why, who, when, and how of the joint naval and military campaigns in the war—the essential work of military strategists.

…in doing the military strategic work of determining what geographic features were most important in war, Mahan’s survey enabled and acted as an example of actual military advice. If military strategists gripe about not having clear political objectives, the corollary gripe of policymakers is that they need military options—that is, they need a clear articulation of what is possible and likely in a given scenario.

Broscino provides some history of how geography used to be taught and an anecdote on how it was applied by looking at Eisenhower.

The education of future Army military strategists used to involve the individual preparation of military geography studies or committee strategic surveys based on military geography. At Fort Leavenworth, students wrote paper after paper on the subject, looking at regions all over the world. At the Army War College, military strategic surveys of the United States and a wide variety of potential theaters of war were a regular feature of the work. For example, Dwight Eisenhower produced reports looking at the eastern United States and Mexico during his year. Similar work went on at the Naval War College.

The practice was of great value. In his wartime memoir, Eisenhower told the story of arriving at the General Staff and being tasked by George C. Marshall to look at the worldwide situation, focusing on the Pacific and the Philippines, to determine “What should be our general line of action?” Eisenhower spent the next few hours coming to his answer, depicted in a couple of succinct pages focused almost entirely on the military geography of the theater (pp. 16-22). The rest, as they say, is history.

You really should read the entire article. My only critique is that this train of thought should not be limited to ‘Military Strategists’ unless you consider individual operators in Special Operations as strategists. Understanding one’s place in the greater fight is crucial to doing your part in achieving victory.

So why is this important and why did I link these two stories together? If you are still with me, join me on this soapbox. These stories, in their own way, reflect the entire Cognitive Warrior Project’s Mission! I believe in the continuing education for war fighters that embrace the adaptation required for tomorrow’s battlefield and think that the fundamental understanding of war must be framed to the general public so they unequivocally know what we are getting into when we send off our next generation to fight. The Cognitive Warrior’s Mission should not be limited to making a better war fighter alone but a more educated public that fully supports our troops beyond slogans and stickers.