I am back! Even though I have been away from the blog I have not been away from the keys. I pseudo volunteered to the write the family history book for this years family reunion and since this is exactly a paid gig…all of my spare time went to that project instead of this. All is not lost however as I was able to clear up some details in regards to my grandfathers service in WWI.

As a family, we always knew that he served but there was a debate on what he actually did during his service. Some thought he never left Iowa and others thought that he may have made it to France shortly after the fighting was over. No one really thought he saw combat and they were proven correct but the story of my grandpa’s service turned out to be far more interesting than I imagined.

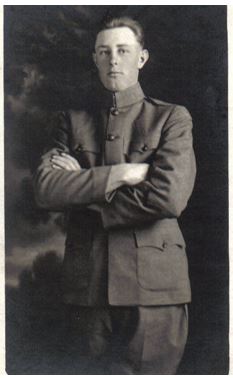

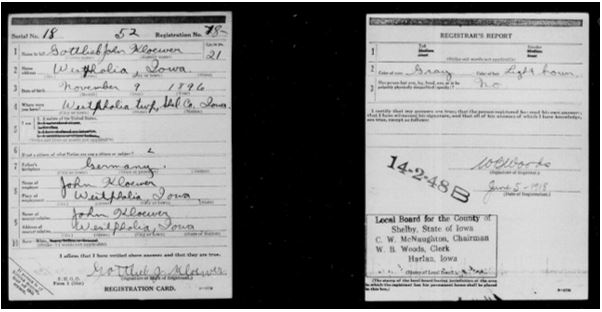

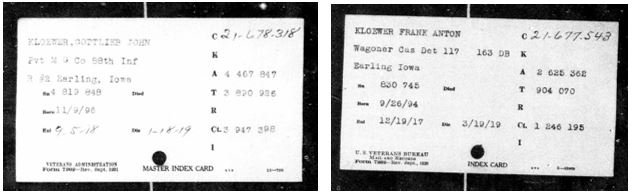

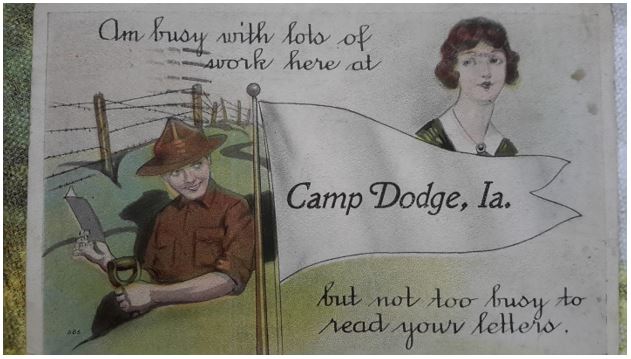

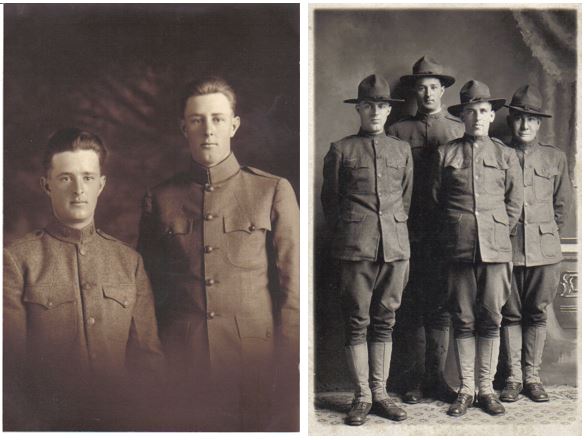

Gottlieb John Kloewer (Sport) was drafted into the service on September 5, 1918, served as a machine gunner in Gulf Company of the 88th Infantry and was stationed at Camp Dodge, IA. There he joined his brother Frank who was drafted into service on December 12, 1917 and served as a Wagoneer for the Hospital Corps. The war would end only two month later on November 11, 1918 and grandpa never saw the front lines of the conflict or even left Iowa for that matter. Family lore was that grandpa was stricken with pneumonia and could not deploy to the fight. I found no evidence that it was the pneumonia that kept him from leaving Iowa but what I did find was unbelievable as the Spanish Flu ravaged Camp Dodge, IA.

From the linked description for that collection, the following codes are listed:

K – Life Insurance

A – Adjusted Compensation (Bonus)

T – War Risk Insurance

R – Rehabilitation

Ct -WWI Certificate

I -Permanent Disability

Here is some the History of Camp Dodge (obtained from Wikipedia):

Original construction of the post began in 1907, to provide a place for the National Guard units to train.[1] In 1917, the installation was handed over to national authorities and greatly expanded to become a regional training center for forces to participate in the First World War.[2]

The name Camp Dodge comes from Brigadier General Grenville M. Dodge, who organized Iowa’s first National Guard unit in 1856.[3] Although not a native-born Iowan, he became a well-known figure and resided within the state for most of his adult life. He is considered a War hero for his service and also served a term as a U.S. Congressman representing the state.

In June 1917, the 163rd Depot Brigade was formed at Camp Dodge.[4] The brigade was the base unit for the 88th Division, which processed new draftees and provided basic training.[5] Later it appears the brigade despatched soldiers to multiple divisions, as two African American soldiers were sent to the 163rd Depot Brigade at Camp Dodge, before being posted to a front-line Pioneer Infantry Battalion in 92nd Division, the “Buffalo Soldiers Division”. The 163 Bgde was still at Dodge in April 1918.[6]

Upon the end of the war, the post was downsized and turned back over to state authorities.[7] Similarly, with the outbreak of the Second World War, Camp Dodge was again handed over to the federal government; however, this time the post was used only as an induction center for new service members.[8] Camp Dodge has served as a Guard and Reserve installation since the end of the Second World War.

Sport was unfortunate to be stationed at Camp Dodge during the height of the Spanish Flu Epidemic which would claim the lives of more than 700 soldiers in 1918. The horror is best described in these excerpts from the Des Moines Register, 3 March 2020

“From the archives: 1918 brought a nightmarish flu epidemic to Iowa’s Camp Dodge” The entire article can be found here:

Editor’s note: More than 700 soldiers at Camp Dodge died of the flu in 1918. At its peak in October 1918, the flu was killing more than 50 soldiers a day. This series of stories by former Des Moines Register Frank Santiago originally published in November 1999.

Part 1: Decades after scourge, the rumors linger

A deadly influenza raced across the Earth in 1918, ultimately claiming 20 million victims. An Army outpost in the middle of Iowa stood in its path. Camp Dodge, just outside Des Moines, smelled of rotting bodies for weeks.

The catastrophe rates only a footnote in state history. What happened in that warm October of 1918 has remained mostly a mystery. The Army refused public comment at the time and quarantined the camp. Daily reports stopped immediately. The story slipped from newspapers and from conversation.

Camp Dodge’s horror is largely lost. No monuments, no plaques in public places mark the state’s worst disaster.

The scourge lives only in obscure spots: worn documents packed in national and state archives, diaries and memories of the few who have followed the camp’s history.

What survive after 80 years are dark rumors and questions: Were flu victims hastily buried in a mass unmarked grave? Were black soldiers who died after being injected with a serum buried near the post hospital?…

The epidemic lurched into Iowa in late September 1918. The flu stories became big news. Postal workers wore masks to handle mail. The Industrial School for Boys at Eldora reported four deaths. Dances and athletic events were canceled. Movie theaters, schools and churches were shuttered or had limited hours.

The flu hit the camp on Oct. 1, 1918. More than 300 soldiers were under observation, records show. A newspaper account four days later said the number of sick had soared to 1,500. Four deaths were recorded. First to die was Pvt. Fennon Landers, a black soldier from Henderson, Kentucky.

The Army ordered soldiers to stay out of pool halls and other public places off the post.

“A large detail of military police is on the job and has orders to request officers found in such places to get out,” an Army memo assured the community.

The epidemic was raging in camp a week after the first case. More than 6,000 soldiers were sick. The crush overwhelmed the camp hospital. Barracks were converted to temporary wards. Some 100 medical officers and 370 nurses struggled day and night.

A camp document said many soldiers who awoke healthy were sick by noon. They were dead before supper.

The stunning speed of death left the camp reeling. Medics worked frantically. Bodies were hauled to trucks, which were driven to ice-filled boxcars near the camp. The dead were stacked in the boxcars and moved to Des Moines for embalming.

Harbach’s Funeral Home, where many of the dead were taken, was swamped. The funeral home pleaded for more coffins and more help.

The Army announced Oct. 9 that it would no longer release daily reports on the disease.

Col. E.W. Rich, the camp’s surgeon, said the details were causing “unnecessary worry” and served “German propagandists.”

Hundreds of telegrams from worried relatives flooded the camp. Rich remained steadfast. The situation was under control, he said Oct. 13.

“It is felt that the epidemic has reached its maximum,” he said, “and is now on the down grade.”

The destruction gained momentum.

One hundred soldiers died of the flu in the first week, official death certificates show. The number jumped by 350 the next week.

The Army lost count as deaths soared. Bodies were sent for embalming without death certificates, an Army investigation revealed. In the beginning, the certificates listed name, age, hometown, race, next of kin and burial site. The details were gradually omitted as paperwork piled up. Hundreds of death certificates eventually had only names and cause of death.

A stunning 450 of Camp Dodge’s soldiers were dead of influenza by mid-October. The dying continued, but there were signs the death plague was sputtering.

A month later, the Army computed the losses: 10,008 cases of flu, 1,923 soldiers with pneumonia, 702 soldiers dead.

Many more probably died. Survivors often developed lung and heart problems. Gorden, the camp museum’s director, estimates the total toll at the base was more than 1,000.

The 702 official deaths swelled the state’s flu toll to 6,500. There were 500,000 flu deaths in the United States.

World War II Gen. Omar Bradley, who served at Camp Dodge as a 24-year-old major, had vivid memories of the devastation.

“The epidemic struck all units of the division, but it appeared to me that those men who had just joined us from Alaska were particularly susceptible,” he said in a 1971 interview. “In the company I brought from Butte, Montana, there were only five flu cases and no deaths. One company from Alaska, which had only 86 men assigned, developed 85 cases and 25 deaths.”

Bradley felt the pain personally.

“Many of my close friends were lost,” he said. “I vividly remember the sad sight of dozens of corpses being taken to the undertaking establishments in Des Moines.”

The epidemic’s impact ended a warm relationship between camp and community. Soldiers who packed Des Moines’ hangouts, theaters and brothels were gone or ordered to stay away. Business owners talked of ruin.

A year later, the Army abandoned the base. Camp Dodge was handed to the Iowa National Guard, which operates it today.

The rumors persisted: Did some of the bodies disappear? Had there been a scandalous experiment on black soldiers?

Part 2: `The dead were everywhere’

Merle Gall delivered fresh milk to flu-plagued Camp Dodge in 1918. The memory hurt more than 80 years later.

Gall, 94, walked into the state’s worst disaster. Hundreds of soldiers were dead or dying from the influenza epidemic at the Johnston post.

“I saw them take soldiers out of there by the truckload. The only thing they had on were their dog tags. They were stark naked.”

Gall, then a teen, faithfully unloaded the milk cans from his father’s Model T and returned home. The grim parade at the camp went on for days.

“They threw them in the trucks like fence posts. They were driven down to boxcars and sent to Des Moines.

“I felt sorry for them,” the retired Osceola farmer said, tears gathering in his blue eyes. “Every day there were bodies. Every day the trucks. You can’t forget that.”

Influenza had spread worldwide and into Iowa. The disease hit especially hard at Army bases, which were packed with soldiers training for World War I. Camp Dodge, with 32,000 recruits at the time, was struck with unforgettable vengeance.

Ultimately, it is unclear if Sport was discharged on January 8, 1919 due to the lack of need or because of a pneumonia caused by the Spanish Flu but he did come home to Western Iowa and returned to life as a farmer. I discovered many other things about my grandpa and family on this project, and how his life, the successes and failures informed who I have become today.